The Black Rock Forest Spring Archeology Event was successfully held in fair weather on Saturday, April 30 and Sunday, May 1 (2022). The event was led by Archaeologist Dana Linck and BRF Forest Historian John Brady at a site called the “Bearmore Site” named after the family thought to have lived there. A spur-of-the-moment schedule extension then saw Dana and John excavate in a cloud on Monday then again with assistance through a hazy Tuesday by hearty returning volunteers Sara Natlo and David Isaacson.

Despite additional excavation time, none of the four test units were completed and another public event is tentatively planned for June (stay tuned!).

Three of the four test units (TU2 – TU4) were placed where stones visible at ground surface may have been remnants of a house foundation. The fourth (TU5) was exploratory and in an area where, among other artifacts, we found additional fragments of a significant military item dating from the Revolutionary War.

The dedicated and enthusiastic help of volunteers in April/May largely exposed many stones in TU3 and TU4. After drawing and photographing them, the stones were removed and the soil beneath further excavated. We found more artifact-laden soil similar to the soil in which volunteers had been digging, but no stones were atop other large stones, and none were set into a builder’s trench as should have been the case for a foundation. It appears the foundation is elsewhere. Possibly, too, the Bearmore residence was supported on a series of small stone piles that our tests have not yet encountered.

Such a foundation portion or support pile may exist in TU2, within which more fieldstone of possible structural use was exposed than in all other tests thus far. Time limitations prevented fully recording all that stone, so record-keeping will be tackled during the next dig session.

A thousand or more artifacts await washing and identification. Most are various types of pottery that date to the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Some of those will be glued together. Other items include bones from food waste, nails, and window glass.

Photographs of just a few artifacts that were just excavated are included with some notes below. Certain ones were selected because they are good examples of commonly found items, while others were chosen for their unusual character and the questions they generate.

Often the most interesting aspect of a site is actually what is not found. One example here is the absence of any brick or mortar rubble found to date. It appears the Bearmore residence hearth and chimney were constructed entirely of local stone, despite the growing Hudson River Valley brick industry. TU5, Lev. 1, 5-1-22

Although in very poor condition, this US Navy button was a surprise find that dates from 1802 to 1830 (Albert 1969:86). The pattern, with an eagle facing right, holding a shield with an anchor on the shield and encircled by 16 stars. The face and back stamped “ARMITAGE . . PHILA . . ” appear nearly identical to one known variant (Albert 1969:97; NA69A). This example differs by having not only the makers mark on the reverse, but also by sporting a series of rings, edge to edge, that surround the central shank. We have some archival research to do before we will have a chance to relate this upland home site to our Navy of the early nineteenth century. That will be difficult, for records of that period require knowing out of what ship or port a person was based.

TU3 Lev. 1

Gold plated convex button with a pattern of triangular “fragments”. It may be from a woman’s coat.

TU5, Lev. 1, 5-1-22

Ribbed olive-green glass vessel fragment, the only one of this form recovered from the site. Possibly we will learn its original purpose after additional pieces are recovered during future digs.

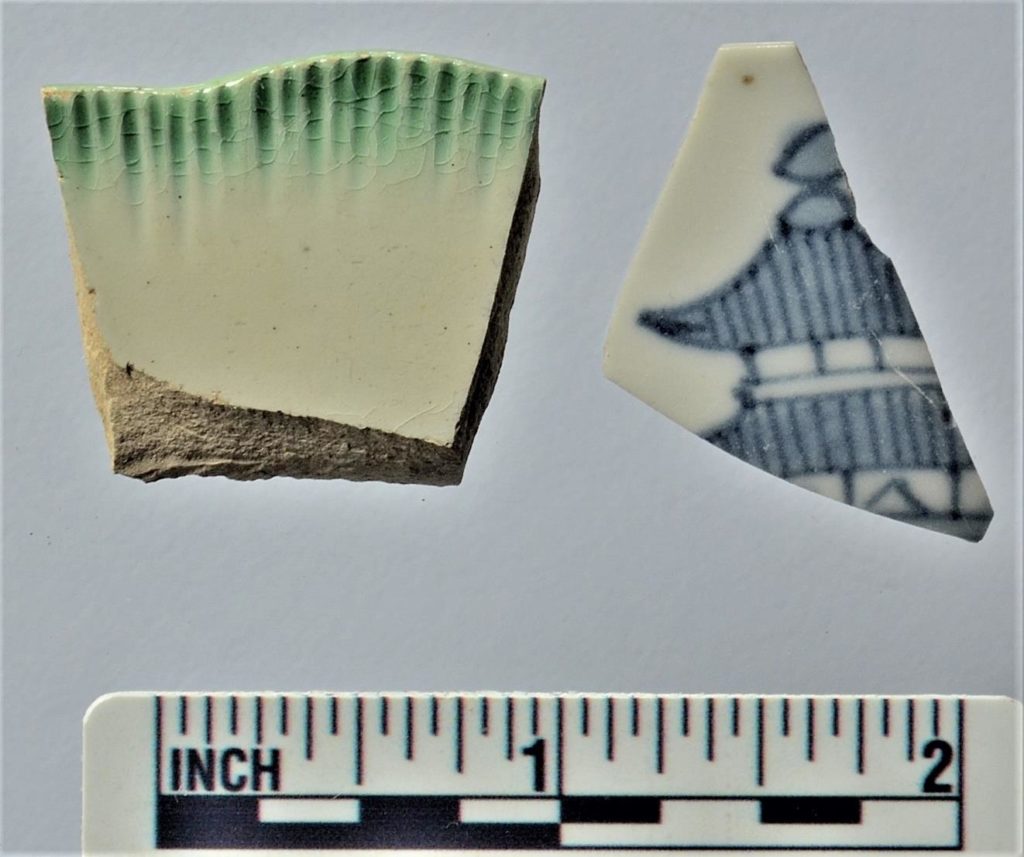

TU3, Lev. 2, 5-3-22

Left: Pearlware (or later white earthenware) green shell edge plate rim (probably English, possibly American). A very common pattern found on many sites dating to the early 19th century. Right: Chinese export porcelain, teacup, or small bowl This is a common early 19th century pattern and, being porcelain, represents an appreciation for the finer things in life.

TU5, Lev. 1, 5-1-22

Possible stoneware porringer base with handle scar (presumed American) This stoneware basal fragment has a wide flaring body above the base rim – very similar in form to the earthenware porringer shown below it. Mugs and pitchers generally do not have as wide a flair.

TU3, Lev. 2, 5-3-22

Posset-cup rim (likely English Staffordshire) Buff-paste, slip-trailed, lead-glazed “posset-cups” for serving food (as well as similar but larger chamber pots often in service a while after serving food) appear to have been imported to the Hudson River valley through the American Revolution and not afterward. Examples shown below are on display at the Fort Montgomery State Historic Site Museum. Note that the Bearmore sherd has a dark brown decorative spot on the rim like the larger chamber pot from the Fort Montgomery display, depicted above, while the rim curvature of the Bearmore sherd indicates a vessel with about an eight-inch diameter – comparable to the smaller possets. It would be unusual for this type of pottery vessel to last in the family from the time of the Revolution to the early 19th century. We suspect its breakage dates to when the nearby Continental Road was built by soldiers in 1780 or by travelers on the road not long afterward.

The Bearmore posset sherd.

Fort Montgomery examples.

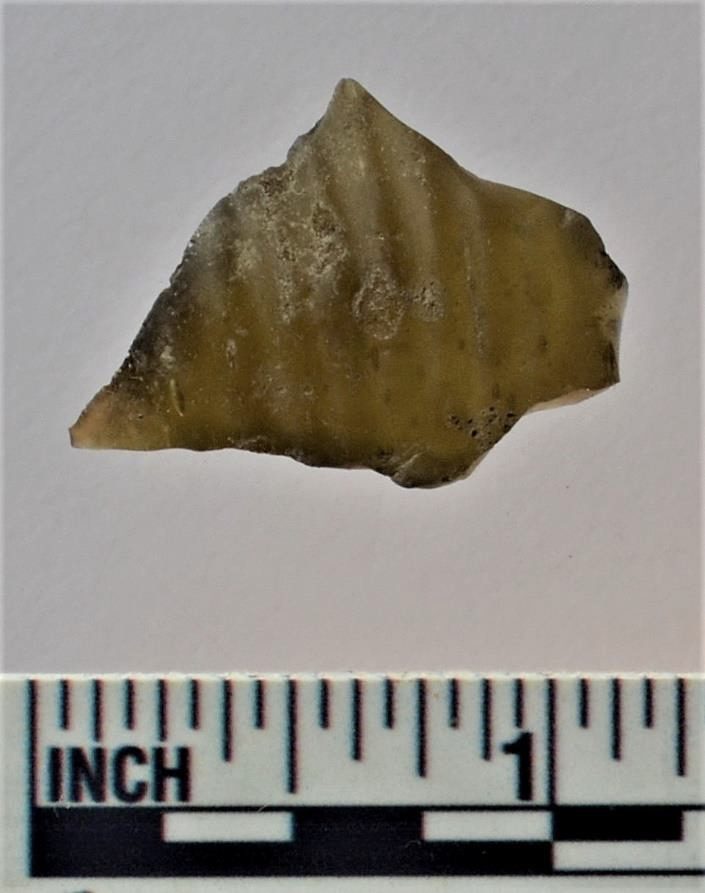

TU4, Lev. 2: Chert-burned, as evidenced by white color and crazing.

TU5 Lev. 1:Quartz flakes

TU5, Lev. 1, 5-1-22:Quartz crystal fragment

TU5, Lev. 2:Dark gray chert: flakes

Flat ground and a permanent water source were magnets for prehistoric occupants in the Hudson Highlands as well as to the historic era Bearmore’s. These fragments of debris from flaking stone tools could be hundreds or a few thousand years old.

To all who visited with a hope of learning a little about archeology, I hope your goals were met. We were thrilled to welcome volunteers of all ages including teens (and at previous events elementary school groups from Black Rock Forest’s Consortium. To all who were also able to shave soil with a trowel or pick out soggy artifacts from our screens, my thanks for your patient and enthusiastic assistance.

Event Recap and Photos by: Dana Linck, Archaeologist